Art, Culture and the "Woman In Gold" Today

- ifafashionblog

- Dec 14, 2020

- 5 min read

Growing up on the Ganges, with echoes of slow trains passing by, my childhood was engulfed in cultural history. Amidst the stories, books, museums and art that seeped through me from my Historian grandmother, I aspired to reach her intellectual excellence. My love for fashion grew while I devoured through the history books of different cultures, revolutions and art movements. Fashion came to me through history, representing the eras of yore.

Paris as we know is a magical dreamland of fashion & art museums, that one gets to experience in a surreal sense. So the idea of art curation in museums today comes to me in more of a preservative mindset. Compared to India’s current state in Art, Design and Fashion preservation in museums, France and particularly Paris becomes a shining beacon for what must be cherished to be taken forward for the future generations to witness and learn.

Since the day I stepped into Paris, I made sure to visit as many museums I could before the pandemic wreathed havoc in my museum-musing journey. I had the privilege of attending Fashion history classes set in the picturesque location of Musée des Arts Décoratifs beside the iconic Louvre. Everyday I walked into the classes, I felt a huge sense of historical accomplishment of walking in my grandmother’s footsteps, leaning more towards fashion.

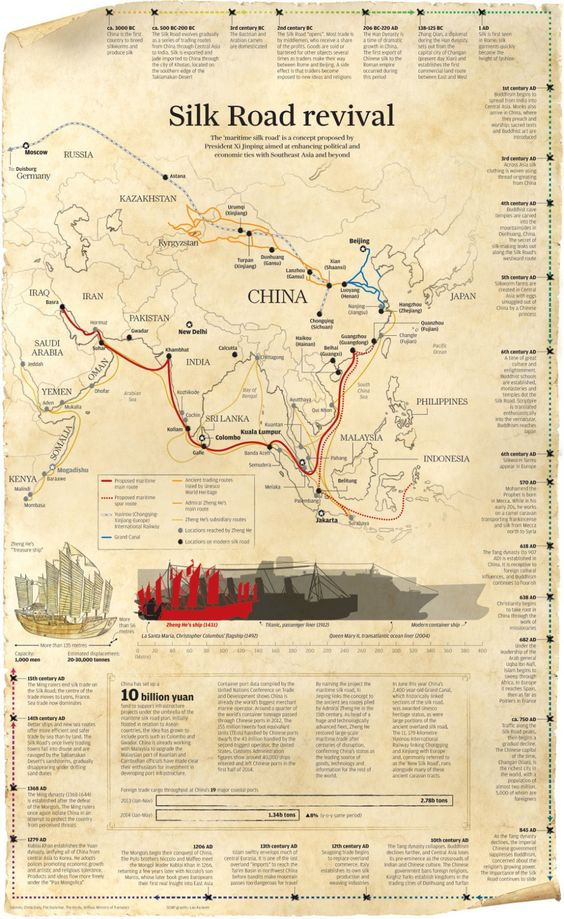

History as we speak through all of its wars and revolutions has shown us proof of how beauty of our created existence and nature is destroyed out of sheer greed. And while speaking of ‘have it all’, ‘war’ and ‘history’ in one sentence, one immediately thinks of countries plundered for wealth and abundances. Before the World Wars, ‘The Silk Route’ was invaluable for European nations, from the silks, spices, condiments and tapestries, to fabrics, precious stones, jewellery and perfumes, all of which came through this abundant trade route traversing India, China, Persia, Arabia, Greece and Italy. But post the disruption of the ‘Silk Route’ the realization of ‘I want it all’ hit a different chord, with the colonization of countries that were filled with precious artifacts, many of whom were of great cultural significance. Today these precious artifacts are placed behind sparkling glass shields of decadent European museums.

For me, this is about a preservation of the past, yet there are many who consider museums as a hall of plundered artifacts of various cultures. And this comes to the forefront in current times where political scenarios are such that there are many cold wars still left unseen in the mass media.

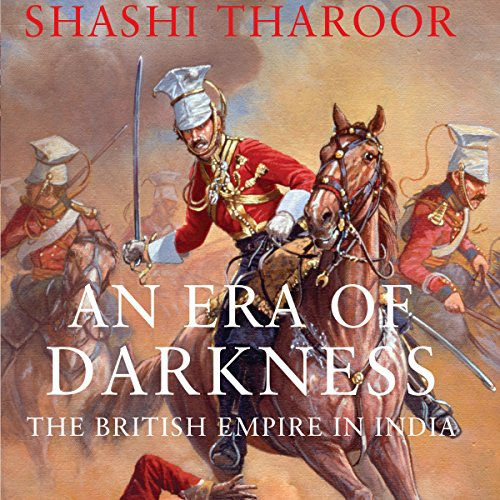

While talking about museums and the cultural artifacts residing in these spaces, I remember an important paragraph from the book ‘An Era of Darkness’ written by one of the most erudite politicians of India, Mr. Shashi Tharoor. He says, “flaunting the Kohinoor on the Queen Mother’s crown in the Tower of London is a powerful reminder of the injustices perpetrated by the former imperial power. Until it is returned—at least as a symbolic gesture of expiation—it will remain evidence of the loot, plunder and misappropriation that colonialism was really all about. Perhaps that is the best argument for leaving the Kohinoor where it emphatically does not belong—in British hands.”

― Shashi Tharoor, An Era of Darkness: The British Empire in India

These words reminded me of a chance conversation I had with two young Persian creatives, one who was raised in France and the other who works in Paris as a creative expat. Jazya, a film director and Zarina, a graphic designer spoke fiercely of how much they despised going to museums. They felt that the superpowers of yore plundered these valuable artifacts from their home countries while they were flourishing. And today while their countries are in a zone of cold war both politically and financially, they have to pay a fee to see what is theirs by culture and origin in a land that looted their wealth. They said people of any culture and origin mustn't be asked to pay a fee in the museums where artifacts are more of stolen or pieces taken out of force. And if there is a fee charged the artifacts rather be given back to the original owner.

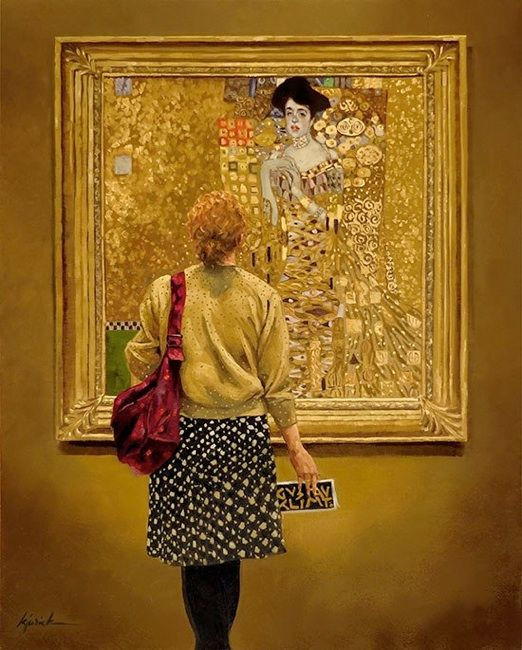

In reference to this passionate conversation with Jazya and Zarina, they mentioned the biographical drama film “Woman in Gold” directed by Simon Curtis which is a film based on the true story of Maria Altmann. Maria Altmann, an elderly Jewish refugee who lived in Los Angeles with her lawyer Randy Schoenberg. And she was known for reclaiming Gustav Klimt's iconic painting of her aunt, Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I that was stolen from her relatives prior to World War II by the Nazis. She fought the government of Austria for a decade and took the legal battle till the Supreme Court of the United States, which ruled on the case Republic of Austria v. Altmann (2004).

Zarina mentions how in the movie the matter of prime importance was “Restitution”. The movie and real-life showcases how the panel hears Altmann’s case in Austria, where her lawyer Schoenberg reminds them of the crimes done under the Nazi regime and requests the arbitration panel to ponder on the meaning of the word "restitution". Ronald asks them to view the artwork hanging in art galleries as the injustice done to the families who were once owners of such great paintings but were separated from them forcibly by the Nazis. Listening to both parties, the arbitration panel rules in favour of Altmann, returning her the paintings but when the Austrian government begs Altmann in a last-minute proposal to keep the paintings in the Belvedere she refusingly chose to have the painting moved to the United States with her ~ "They will now travel to America like I once had to as well".

The movie and the feeling expressed were in sync with how Jazya and Zarina felt. And despites the times we are living in, it makes us ponder what would happen if all the artifacts of different cultures are asked to be returned to their respective countries of origin?

To add on to this discussion, I end with Shashi Tharoor's Oxford Union speech on 28 May 2015, which is one of Oxford Union’s most watched debate speech videos with over 7 million views on YouTube (as of July 2020). The excerpts of the winning speech go like this -

“ The proposition before this house is the principle of owing reparations, not the fine points of how much is owed, to whom it should be paid. The question is, is there a debt, does Britain owe reparations? As far as I am concerned, the ability to acknowledge your wrong that has been done, to simply say sorry will go a far far far longer way than some percentage of GDP in the form of aid. What is required it seems to me is accepting the principle that reparations are owed.” — Shashi Tharoor

So after these impassioned thoughts on art of various cultures present in the Museums of Europe and Britain, what does reparation mean to you ? Is it truly necessary to keep the work of hostile or politically disrupted nations, for reasons of safety and preservation? And does protection of these valuable artifacts lie only in the hands of the few historically dominant and respected nations?

These questions will raise many eyebrows, they may make you feel uncomfortable and even reflect on different sides of this intriguing cultural debate.

Comments